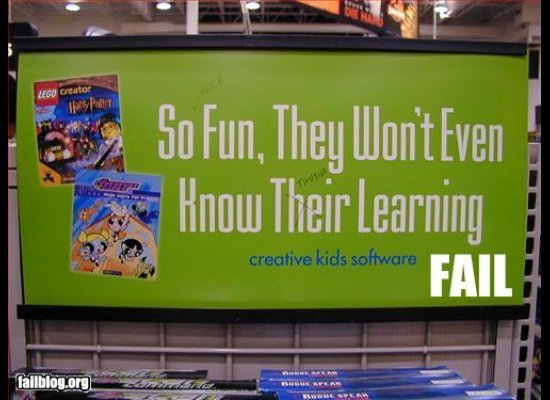

When it comes to "fails" it doesn't get much worse than those that are education related. We know nobody's perfect when it comes to typos, but if you are a place of learning you should at least be able to get your signage, text books, and students' work fail-free. These are some of the WORST education fails we could find. How smart do you feel now? Take a look and vote for the worst!

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

The WORST Education Fails Of All Time (PHOTOS)

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Op-Ed Columnist - The Billionaires Bankrolling the Tea Party

Friday, August 20, 2010

Thursday, August 19, 2010

White House Memo - In Defining Obama, Misperceptions Stick

Monday, August 16, 2010

NSF Misfires on Plan to Revamp Minority Programs

23 JULY 2010 VOL 329 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org /Published by AAAS/ *NSF Misfires on Plan to Revamp Minority Programs* Everybody agrees that U.S. colleges and universities need to prepare more minority students to enter careers in science and engineering. But almost nobody likes a new plan by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to fold three programs aimed at achieving that goal into a still-to-be-defined initiative. Scientists and university administrators involved in the programs are up in arms, and Congress is telling NSF to go back to the drawing board. NSF currently spends $90 million a year on three efforts tailored to institutions that serve African Americans and American Indians: the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP), the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Undergraduate Program, and the Tribal Colleges and University Program. Last year, a U.S. House of Representatives spending panel told NSF to design a fourth program specifically for the nation’s Hispanic population, the nation’s largest underrepresented minority. That step could quadruple the pool of eligible minority-serving institutions. At the same time, as part of a larger campaign to eliminate redundancy in government, budget officials in the Obama Administration began urging NSF to streamline its stable of programs aimed at increasing the participation of underrepresented minorities in so-called STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields. In an attempt to resolve the conflicting guidance, NSF requested a bit more money— $103 million—in its 2011 budget for a new initiative that it awkwardly labeled Comprehensive Broadening Participation of Undergraduates in STEM. “We felt we had reached a plateau in college graduation rates, in Ph.D. production, and in transition to the professoriate,” says *James Wyche (an ASI Fellow), who headed the NSF division that runs the three minority programs before becoming *Provost and Chief Academic Officer* of Howard University in Washington, D.C.*, earlier this year. “So the question was, do you stay the course or look for something else?” The specific suggestion to combine programs came from the White House, he adds. “OMB [The Office of Management and Budget] encouraged us to think about a program that would consolidate what we were doing to broaden participation among the targeted groups, something that would use the best practices from each one.” The bare-bones budget announcement, unveiled in February, didn’t provide any details. In May, NSF issued a 5-page concept paper (http://www.nsf.gov/od/ broadening participation/bp.jsp) that declared the existing programs “should serve as a foundation for a new approach,” meaning they would be dissolved. It also said that Hispanic-serving institutions, a poorly defined term for schools at which Hispanic students constitute a significant share of the overall enrollment, would be invited to seek funding. Major research universities, now partners in some existing projects run by minority serving institutions, would be eligible to apply directly to NSF as the lead institution. Although the paper asks for advice on how to proceed, the community had heard enough to ring the alarm. For openers, say critics, the three programs are working: Outside evaluations confirm that they are attracting and graduating more minority students. The programs have also developed an approach that can be scaled up. So university administrators say they don’t understand why NSF would want to dilute them. Opponents of the NSF plan also attacked the inclusion of the nation’s top research universities. That change would not only open the door to institutions with a poor track record of training minorities in science and engineering fields, they said, but also give those schools an advantage because of their vastly superior resources. Finally, critics complained, NSF hadn’t offered any evidence that a different approach to training minority scientists would work better. Last month, the 42 consortia in the LSAMP program told NSF they strongly oppose the changes. Stephen Cox, provost of Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and director of a project involving nine local and regional institutions, says he also wonders why NSF has put the burden for broadening participation in science on these three, relatively tiny, programs. “Rather than squeezing more blood from this stone,” Cox said, “why doesn’t NSF get some more stones?” Congress doesn’t care much for NSF’s new idea, either. This spring, the House of Representatives, as part of its reauthorization of the America COMPETES Act that covers NSF’s research and education activities (H.R. 5116), told NSF to keep the three programs intact in 2011 and submit a report “clarifying the objectives and rationale for such changes” before heading off in a new direction. “It’s something they had not discussed with us,” says Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D–TX), a senior member of the House science committee, who crafted the language on the minority programs. “I think they need to discuss it with stakeholders, who told me that it seems like a way to cut a lot of money from these programs.” A Senate version of the reauthorization bill introduced last week (S. 3605) would also preserve the programs, and a House spending bill for 2011 likewise tells NSF to keep funding them. NSF appears to be rethinking its strategy. Joan Ferrini-Mundy, acting head of NSF’s education directorate, which oversees these programs, says NSF is looking hard “at what a transition would actually look like. A lot is still on the table.” She also notes that “broadening participation is an NSF-wide commitment” and that any final plan is likely to involve the agency’s six research directorates as well. *–JEFFREY MERVIS*

Senior archivist of African-American writing for Chicago Public Library's Harsh Research Collection retires

Senior archivist of black history to retire after years at Chicago Public Library's Harsh Research Collection

Michael Flug, senior archivist for the Chicago Public Library's Harsh Research Collection, speaks Friday at a news conference to announce the addition of papers from the Rev. Addie Wyatt and Rev. Claude Wyatt. (Chris Salata, Photo for the Chicago Tribune / July 31, 2010)

Senior archivist Michael Flug helped build a vast collection of African-American history and literature

Dawn Turner TriceAugust 9, 2010

ct-met-trice-flug-0809-20100808

Often, when a person announces his retirement, the "congratulations" follow. But that hasn't exactly been the case for Michael Flug, the senior archivist with the Chicago Public Library's Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection who will retire next month after 21 years of service.No, most of the people have either grimaced or gone slack-jawed. One friend, a television producer who has relied on Flug for years, said to me, "Lord, I have to sit down."

That's exactly the way I felt when I received the news, which came mid-July in the form of an e-mail invitation to his going-away party later this month.

You might not know Flug's name, but if you've read a news story or book, or even watched a documentary dealing with black history in Chicago, chances are you've encountered archival information that he has either assembled or shepherded.The Harsh Research Collection, housed in the Carter G. Woodson Library Branch, is believed to be the largest collection of African-American history and literature in the Midwest.

That's thanks to Flug and a staff that includes another archivist, a curator and two reference librarians, as well as "friends" of the collection whose contributions have made Harsh an enormous repository of material: rare books, magazines, sheet music, microfilm, photographs and clippings you won't find anywhere else. Harsh also has more than 200 collections of archives and manuscripts.

Flug is a self-described curmudgeon who shuns the limelight and praise, but the researchers I've directed his way have all returned to me wowed by his unique insights and perspective, and the way he treated their projects with a zeal and enthusiasm one normally reserves for his own.

But it's not just bigwigs who receive the full measure of his expertise.

"I'm just as proud of the high school students who do great history projects as the college professors who write fine books," Flug told me as we visited last week in the library.

Flug, 65, grew up in New York, the son of Jewish immigrants. He joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in New York in 1960 and worked in several states, including Mississippi. He left there in 1968 to work for Detroit's Human Rights Department before coming to Chicago in 1990 to work for Harsh.

As an archivist of African-American history, Flug has been able to meld his passion for social justice work with his desire to safeguard precious memorabilia that had been shunted into the alcoves of church basements, apartment closets or damp lofts.

For three years, Flug made weekly visits to the Hyde Park apartment of activist and educator Timuel Black, now 91. Flug labored through 70 years worth of hip-high stacks that included photographs and correspondences from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mayor Harold Washington.

The material is now in 250 document cases, and the staff is nearly finished processing the collection, which is scheduled to open to the public in October.

Perhaps one of Flug's greatest contributions was Harsh's 1998 "Chicago Renaissance" exhibit that examined the cultural flowering of black Chicago in the 1930s, '40s and '50s in art, music, journalism, literature, the social sciences and even social protest.

"We decided that because we already had collections of people who participated in the Chicago Renaissance, we were going to show how it differed from the Harlem Renaissance and how multidimensional it was, and the international impact it had," Flug said.

The exhibit ran for two years, and donations from others who had been involved in the movement poured into the Harsh collection.

On Friday, Flug joined Mayor Richard Daley and others at the Harold Washington Library Center to announce the opening of the "Rev. Addie Wyatt and Rev. Claude Wyatt Papers." With 345 boxes of memorabilia, it's the largest collection ever processed by Harsh and chronicles the lives of Claude Wyatt, a seminal civil rights figure in Chicago, and Addie Wyatt, a labor activist and leader in the civil rights and women's rights movements.

Flug told me that his approach to black history comes from Carter G. Woodson, the early 20th century scholar, historian and author, who believed that the presentation, study and dissemination of black history could change race relations and make this a better country.

"To that end, this has never just been a job to me," said Flug, who hopes to return to Harsh on a part-time basis. "The work is not an abstract enterprise or confined to the ivory tower. I am a very lucky and blessed man because if I look at the universe of jobs I could have had, there's none better suited to me than this one."

Indeed. And, by the way, congratulations, my friend!

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

NSF Misfires on Plan to Revamp Minority Programs

Date: Tue, 10 Aug 2010 16:46:51 -0400

From: Lee O. Cherry of the African Scientific Institute <asi@quixnet.net>

*Your Thoughts? *

23 JULY 2010 VOL 329 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org /Published by AAAS/ *NSF Misfires on Plan to Revamp Minority Programs* Everybody agrees that U.S. colleges and universities need to prepare more minority students to enter careers in science and engineering. But almost nobody likes a new plan by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to fold three programs aimed at achieving that goal into a still-to-be-defined initiative. Scientists and university administrators involved in the programs are up in arms, and Congress is telling NSF to go back to the drawing board. NSF currently spends $90 million a year on three efforts tailored to institutions that serve African Americans and American Indians: the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP), the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Undergraduate Program, and the Tribal Colleges and University Program. Last year, a U.S. House of Representatives spending panel told NSF to design a fourth program specifically for the nation’s Hispanic population, the nation’s largest underrepresented minority. That step could quadruple the pool of eligible minority-serving institutions. At the same time, as part of a larger campaign to eliminate redundancy in government, budget officials in the Obama Administration began urging NSF to streamline its stable of programs aimed at increasing the participation of underrepresented minorities in so-called STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields. In an attempt to resolve the conflicting guidance, NSF requested a bit more money— $103 million—in its 2011 budget for a new initiative that it awkwardly labeled Comprehensive Broadening Participation of Undergraduates in STEM. “We felt we had reached a plateau in college graduation rates, in Ph.D. production, and in transition to the professoriate,” says *James Wyche (an ASI Fellow), who headed the NSF division that runs the three minority programs before becoming *Provost and Chief Academic Officer* of Howard University in Washington, D.C.*, earlier this year. “So the question was, do you stay the course or look for something else?” The specific suggestion to combine programs came from the White House, he adds. “OMB [The Office of Management and Budget] encouraged us to think about a program that would consolidate what we were doing to broaden participation among the targeted groups, something that would use the best practices from each one.” The bare-bones budget announcement, unveiled in February, didn’t provide any details. In May, NSF issued a 5-page concept paper (http://www.nsf.gov/od/ broadening participation/bp.jsp) that declared the existing programs “should serve as a foundation for a new approach,” meaning they would be dissolved. It also said that Hispanic-serving institutions, a poorly defined term for schools at which Hispanic students constitute a significant share of the overall enrollment, would be invited to seek funding. Major research universities, now partners in some existing projects run by minority serving institutions, would be eligible to apply directly to NSF as the lead institution. Although the paper asks for advice on how to proceed, the community had heard enough to ring the alarm. For openers, say critics, the three programs are working: Outside evaluations confirm that they are attracting and graduating more minority students. The programs have also developed an approach that can be scaled up. So university administrators say they don’t understand why NSF would want to dilute them. Opponents of the NSF plan also attacked the inclusion of the nation’s top research universities. That change would not only open the door to institutions with a poor track record of training minorities in science and engineering fields, they said, but also give those schools an advantage because of their vastly superior resources. Finally, critics complained, NSF hadn’t offered any evidence that a different approach to training minority scientists would work better. Last month, the 42 consortia in the LSAMP program told NSF they strongly oppose the changes. Stephen Cox, provost of Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and director of a project involving nine local and regional institutions, says he also wonders why NSF has put the burden for broadening participation in science on these three, relatively tiny, programs. “Rather than squeezing more blood from this stone,” Cox said, “why doesn’t NSF get some more stones?” Congress doesn’t care much for NSF’s new idea, either. This spring, the House of Representatives, as part of its reauthorization of the America COMPETES Act that covers NSF’s research and education activities (H.R. 5116), told NSF to keep the three programs intact in 2011 and submit a report “clarifying the objectives and rationale for such changes” before heading off in a new direction. “It’s something they had not discussed with us,” says Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D–TX), a senior member of the House science committee, who crafted the language on the minority programs. “I think they need to discuss it with stakeholders, who told me that it seems like a way to cut a lot of money from these programs.” A Senate version of the reauthorization bill introduced last week (S. 3605) would also preserve the programs, and a House spending bill for 2011 likewise tells NSF to keep funding them. NSF appears to be rethinking its strategy. Joan Ferrini-Mundy, acting head of NSF’s education directorate, which oversees these programs, says NSF is looking hard “at what a transition would actually look like. A lot is still on the table.” She also notes that “broadening participation is an NSF-wide commitment” and that any final plan is likely to involve the agency’s six research directorates as well. *–JEFFREY MERVIS*

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Editorial - In Search of a New Playbook

EDITORIAL

In Search of a New Playbook

Published: August 7, 2010

In less than 90 days, millions of irritable voters will go to the polls to choose a new House and much of the Senate. If Democrats hope to retain control of both chambers in a year of deep dissatisfaction with incumbents, they need a sharper and more inspirational playbook than the one they are using.

Political forecasters have warned for months that the widespread anti-Democratic sentiment in the nation could well coalesce into a Republican wave that approaches that party’s gains in 1994. President Obama’s independents have deserted him, the business and Tea Party wings of the Republican Party are alight with fervor and cash, and even season-ticket Democrats are searching for their old enthusiasm.

In part, that is because the significant accomplishments of the last two years — health care reform, the stimulus package, the resuscitation of the auto industry, financial reform — were savagely attacked by the right and aggressively misrepresented as the hoof beats of totalitarianism. Most of those efforts were actually highly diluted to draw centrist support, but they did not really get much of it, and the compromises meant that the bills were defended only halfheartedly by Democrats who should have stood up more firmly to the rage.

Put most broadly, the Democrats have been failing to delineate the differences between themselves and Republicans, to remind voters what Republicans would do if returned to power and how little their policies have changed from those during the two terms of President George W. Bush.

Recently, this has started to change. President Obama has become uncharacteristically combative, delivering a series of ardent speeches that other Democrats would do well to imitate. In remarks at a Democratic fund-raiser in Atlanta last Monday, he pointed out that Bush-era Republicans had cut taxes for millionaires, cut rules for special interests, and cut loose working people to fend for themselves.

Since then, he said: “It’s not like they’ve engaged in some heavy reflection. They have not come up with a single solitary new idea to address the challenges of the American people. They don’t have a single idea that’s different from George Bush’s ideas — not one. Instead, they’re betting on amnesia.”

Democrats could start to banish that haze of memory by reminding voters what is actually in those giant packages of legislation: Protections for patients against insurance companies. Rules keeping adult children on health policies, and requiring coverage for pre-existing conditions. A new consumer financial protection bureau to fight lending abuses. The preservation or creation of nearly three million jobs, averting Depression-level unemployment. The local benefits of stimulus projects.

Republicans fought against each of those measures, and seem to be spoiling to hold hostage middle-class tax cuts in order to preserve tax cuts for the rich. Democrats have been far too timid in taking on those issues, to the point that they now will have to do more than simply remind voters of Republican opposition.

For most voters, the only real issue is high unemployment, and it is here that Democrats seem to have set aside bold thinking and fallen into the Republican trap of placing deficit fears ahead of job revival. Rather than spend time during the campaign stoking anxiety over Social Security, Democrats should aggressively counter the myth that the deficit is causing unemployment, and advocate using government in ways that might re- inspire voters.

A few suggestions: Using the revenue from reinstating taxes on the rich to put people back to work, rebuilding and repairing the country. Providing robust support for state and local governments, many of which have cut past the bone. Repairing the unemployment system so that it is a real safety net and not a political tool.

As the economy recovers, there will be money available for sane and careful deficit reduction, territory the Democrats know far better than their opponents. A House or Senate controlled by Republicans, leading to longer stalemates and years of political posturing, is not the way to get there. Instead of shrinking from their accomplishments, Democrats should use their remaining time to build on them.

A version of this editorial appeared in print on August 8, 2010, on page WK7 of the New York edition.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Female gamers: Recruiting women as game developers

Women missing from video game development work force

Although many women are gamers, few think to make a career out of their hobby

Keisha Howard, center, of Chicago, plays video games during a Sugar Gamers meet up at Play N Trade in Chicago. (Andrew A. Nelles, for Chicago Tribune / August 5, 2010)

By Wailin Wong, Tribune Newspapers9:57 p.m. CDT, August 5, 2010

sc-biz-0806-women-gamers-20100805

In certain corners of the gaming world, women are treated in one of two ways.

"If you let anyone know you're a girl, you're going to get hit on or picked on," said Tracy Fullerton, a professor at the University of Southern California who teaches game design.

Fullerton was referring to online shooter games, which are traditionally male-dominated. In reality, gaming in general has opened up to women in the last several years, a shift that is part of the industry's broadening appeal to a wider range of ages and tastes.

But while women are playing in greater numbers, working in the industry can feel as lonely as battling aliens on a remote planet in Halo.

According to the Entertainment Software Association, 40 percent of video and online game players in the U.S. in 2010 are female, having inched up from 38 percent in 2006. The number of women working as game developers, however, is much smaller. In a 2005 demographic survey by the International Game Developers Association, only 11.5 percent of the respondents were female.

At Columbia College, Mindy Faber was shocked to discover that the school's 2009 graduating class of game design majors had one woman out of 26 students. The ratio barely improved in subsequent classes, inspiring Faber to organize a four-day summit about girls, gaming and gender that will take place at Columbia next week.

"Our feeling in our department is that clearly, we can make better games if we diversify the designers," said Faber, academic manager in the department of interactive arts and media. "If the game designers out there are more inclusive and representative of our general culture, we're going to make better games that reach more people."

One gap that needs to be addressed, Faber said, is that young girls who like video games don't connect their leisure activity with a potential career path.

This was the case with Megan-Alyse O'Malley, who came to DePaul University as a secondary education major. During her freshman year, she attended an event sponsored by DeFRAG, the campus organization for gamers and developers. Her involvement with the group eventually led her to enroll in introductory game development classes.

The experience of "sitting down with a team, brainstorming ideas on what makes a game fun, then working on my first game project" hooked O'Malley, 21, who had grown up playing console games with her siblings. She is now majoring in Japanese studies with a minor in game design.

"I just fell in love with it," said O'Malley, who will be DeFRAG's first female president when she returns to school this fall for her senior year. She is also the producer and lone woman on a 20-member student team that is entering a worldwide game development competition next year.

Recruiting more women such as O'Malley to the industry often involves a shift in mindset so that students understand they can create games for new platforms such as mobile phones and social networking sites, said Jose Zagal, an assistant professor at DePaul.

"When people say video games, a lot of (students) think PlayStation 3," Zagal said. "When you say, 'What about a game like 'Club Penguin' or 'Farmville' or that game on your cell phone?' Then they're excited."

Women in the game industry have historically worked in departments such as marketing and public relations, rather than in development, art and programming — areas that are directly involved with making games, said Belinda Van Sickle, chief executive of Women In Games International.

"There were a lot of assumptions about women," Van Sickle said. "People in the industry would assume you don't play games, or if you do, you're kind of weird or play games they don't think count."

This assumption may be why "female" games often fail to resonate with their intended demographic.

"The games that are marketed to females are awful," said Keisha Howard, a 26-year-old Chicagoan who founded Sugar Gamers, a local meet-up group for female players. "It's like 'Cooking Mama,' fashion design, pink-little-pony-puppy-kitten. I don't want to play any of those games, ever. I believe women like the games that are most popular, the blockbuster hits."

Last year, the top-selling computer game by units was "The Sims," according to the NPD Group. The game, which allows users to create intricate virtual worlds, is the current obsession of 15-year-old Mary Gilmore. She loves the creativity and detail that goes into playing it, and used to carry around journals to sketch out her house designs before transferring them online.

"It's not, 'There are girl games and boy games,'" said Gilmore, an incoming junior at Evanston Township High School. "It's that there are good games and bad games."

This is also the viewpoint of Erin Robinson, an independent game designer in Naperville. She graduated from college with a degree in psychology and began creating games after discovering free, downloadable tools on the Web.

"I don't really know what female players want, but I know what I want in a game," said Robinson, who will be speaking at the Columbia College summit.

Fullerton, the University of Southern California professor, will also be participating in the summit. She said she hopes the event will showcase female role models and the rich variety of games being created in the industry.

"Now we have families that are growing up playing games together," Fullerton said. "Obviously, we had that in the past in board games, and now we have that in a digital sense. That kind of connection to games as an important element of your family and social life will make people feel differently about the potential they could bring to the industry."

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

Comments (16)

Add / View comments | Discussion FAQdavid.osedach at 3:59 PM August 06, 2010If I had the time - I'd gladly join them!

emilymugler at 3:21 PM August 06, 2010Check out the language on this, everyone:

"Although many women are gamers, few think to make a career out of their hobby"

How about, "few CHOOSE to make a career out of their hobby"? As a female engineer, and someone that is always trying to encourage more young women to pursue math and science, it really doesn't help the cause when it looks like "oh, it hadn't occurred to us"

Buster Cap at 3:06 PM August 06, 2010Women can't program. But they can and should help with the artwork, voicework, animation, etc.

Convicted felon has become an impassioned advocate for the rights of people with criminal records

From practicing law to changing it

Michael Sweig's work as a public policy liaison for the Safer Foundation helps give ex-offenders a chance to get back on their feet. (Phil Velasquez, Chicago Tribune / July 25, 2010)

Former attorney and convicted felon works to give ex-offenders a second chance

Dawn Turner Trice5:14 p.m. CDT, August 1, 2010

ct-met-trice-0802-20100801

In 1991, Michael Sweig had been practicing law for nearly five years when he decided to leave his Chicago law firm and six-figure salary to hang out his own shingle."In hindsight, I was an entitled, greedy bastard," said Sweig, now 51. "I was making over $100,000 a year, and I thought that was a pittance. I was just out of control. My moral compass and judgment skills were pointing completely south."

What happened next explains why Sweig has become an impassioned advocate for the rights of people with criminal records. It explains why instead of working as an attorney, he teaches legal studies and works as the public policy liaison for the Safer Foundation, which helps ex-offenders find jobs.

It also explains why he was the best person at Safer to help shepherd legislation last year that expanded the pool of offenses eligible for the court-granted certificate of good conduct that gives ex-offenders an opportunity to apply for jobs previously off-limits.Sweig has a personal stake because Sweig himself is a convicted felon.

"Here I was, this guy who grew up in Highland Park, got the great education (a law degree) from DePaul University and had a great family," Sweig said. "I started my own law firm and got into a huge mess with my biggest client. I started doing stuff you just can't do if you're a lawyer."

When the big client refused to pay a substantial legal fee, Sweig started using trust account money to run the firm. Though his former law partner bailed out the firm, they couldn't recover from the loss of revenue — especially with Sweig paying himself way too exorbitantly from the firm's coffers.

"Things got tense, and with the advice of counsel, I came to the conclusion that the only choice I had was to turn in my law license, voluntarily," he said.

Sweig was never arrested. His lawyer went to the state's attorney and struck a deal that resulted in Sweig pleading guilty to one count of theft. The firm closed in 1997.

Sweig said it was the combination of following his attorney's advice and his former partner making everything right with their clients that kept him from going to prison. But his life took a dramatic turn.

Sweig was sentenced to a year of home confinement, four years of probation and 500 hours of community service. His family — his two daughters and his then-wife — went from living in a spacious home in Glencoe to an apartment over a nearby deli.

Back when he was the cocky young litigator, Sweig never thought he would know firsthand how difficult it was for a felon to find a job or for a white-collar criminal to get support services sometimes more readily available to ex-cons who are poor and not well-educated.

In 1998, Sweig was fortunate enough to work long distance as a paralegal for his father, who had a law firm in Colorado, back when disbarred attorneys could do such work. After that, he found jobs in Chicago — teaching, arranging real estate investments and working briefly as a rental agent on a temporary license.

But Sweig couldn't get the permanent license, though he said he passed the test, because of his background.

"There are roadblocks everywhere," Sweig said. "But you must be the one who outs yourself. The worst thing you can do is try to hide it. Once you're rehabilitated, the issue should be what have you done since you got in trouble, not what did you do to get in trouble."

Sweig stresses that studies show employment reduces criminal recidivism. He traveled to Springfield 13 times to advocate for the changes to the law that allows for the certificate of good conduct. He believes the program promotes rehabilitation by forcing the ex-offender to talk about his or her life changes before a circuit judge. The person has to prove a second chance has been earned.

Because Sweig voluntarily gave up his law license, the mandatory timeout was for three years. He's been able to petition for reinstatement since summer 2001. But right now he prefers teaching. He's taught part time at Kendall College, DePaul University and Roosevelt University. And he recently discovered advocacy.

"Lobbying and public policy advocacy is a godsend for me because there are no barriers for felons, and I can draw on all my training and my education," Sweig said.

"I'd rather spend my time succeeding at something I'm good at instead of chasing something that was so toxic for me. … I gave up trying to be the richest guy in the graveyard."

Comments (0)

Add comments | Discussion FAQCurrently there are no comments. Be the first to comment!

Copyright © 2010, Chicago Tribune

Current or Former Lawmakers Linked to Endowments Made by Corporations

Corporate Money Aids Centers Linked to Lawmakers

By ERIC LIPTON

WASHINGTON — Nearly a dozen current or former lawmakers have been honored by university endowments financed in part by corporations with business before Congress, posing some potential conflicts like that attributed to Representative Charles B. Rangel in an House ethics complaint.

The donations from businesses to the endowments ranged from modest amounts to millions of dollars, federal records show. And the lawmakers, who include powerful committee chairmen or party leaders, often pushed legislation or special appropriations sought by the corporations.

An endowed chair at the University of Hawaii honoring Senator Daniel K. Inouye, the Hawaii Democrat and chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, was financed in part by $100,000 from a cruise ship line that the senator helped with legislation allowing it to expand its American ports of call.

A program at South Carolina State University named for Representative James E. Clyburn, the third-ranking House Democrat and a key backer of legislation to promote new nuclear power plants, stands to benefit from donations by Fluor and Duke Energy, which want to build plants.

And an endowment at the University of Louisville intended as a tribute to Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican minority leader, has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from a military contractor that later got a $12 million earmark sponsored by the senator.

Companies and lawmakers defend the donations as simply contributions to a good cause, but critics charge that they are a way for businesses to influence lawmakers in addition to campaign contributions, and without the limits or required disclosures.

“It is another way to curry favor — and a less visible one,” said Melanie Sloan, executive director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “But it can perhaps be even more effective, because the sums can be much vaster, and it really feeds the members’ vanity as these centers are something that will last in perpetuity.”

Mr. McConnell and other lawmakers reject any similarity to Mr. Rangel’s activities, and say the donations have no bearing on their conduct.

“Any efforts to draw comparisons with Mr. Rangel are absurd,” said Don Stewart, a McConnell spokesman, who added that the senator’s support for any earmarks was unrelated to donations. “It is without similarity whatsoever.”

None of the dozen lawmakers appear to have linked their office to the endowments as closely as Mr. Rangel, the New York Democrat, is accused of doing by a House ethics panel. Mr. Rangel, who has been forced to step down as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, used Congressional letterhead to send out solicitation letters urging companies with business before his panel to donate to a program honoring him at the City University of New York. He even discussed the legislative matters at meetings where he was soliciting donations, according to the House ethics complaint. In at least one case, he helped a donor get a requested tax break.

Mr. McConnell, though, like Mr. Rangel, met with business leaders to solicit contributions to his center, an aide said, adding that the fund-raising effort ended before he became Senate minority leader in 2007. Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, while in office, also personally hosted a fund-raising dinner, soliciting contributions for an oral-history program that will be part of his institute.

Several of the university programs — including those honoring Mr. Clyburn and former Speaker J. Dennis Hastert, Republican of Illinois — are intended to include the lawmakers’ archives, which the House ethics committee in the Rangel case has called a personal benefit to the congressman.

There is no comprehensive list of these programs, since members of Congress are not required to disclose them. Several lawmakers and universities declined requests by The New York Times and other newspapers to reveal a full list of donors or fund-raising events that the members of Congress participated in. The Times survey focused on endowments or educational programs established while the lawmakers were still in office. There are no limits on such memorials being created after a member of Congress retires or dies.

Education officials involved in creating these centers said they had been amazed at how quickly they had been able to raise money for programs named for a sitting member of Congress. At the University of Hawaii, $1.6 million was donated in the first month of fund-raising for the endowed chair honoring Mr. Inouye and his wife, a record for the university. More than 25 of the donors — government contractors, banks, insurance and telecommunications companies — gave at least $25,000, far more than would be permitted in a single year of campaign contributions. An aide to Mr. Inouye said the donations had no influence on his legislative positions.

Some gifts have come in extremely large chunks — like the $1 million donated in 2005 by Northrop Grumman, the miltary contractor, to help establish the Trent Lott National Center at the University of Southern Mississippi. Mr. Lott, a Republican from Mississippi, served in the Senate until 2007.

The Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate drew a $5 million donation from Amgen, the drug company, as Mr. Kennedy was pushing legislation in 2009 granting biotech companies like Amgen greater market protections from generic drugs. The institute has raised $55 million in private money, much of it donated after Mr. Kennedy’s death last year.

Many donors have specific agendas for which they are seeking lawmakers’ help. For example, FMC Corporation, a chemical company based in Philadelphia, has made at least three contributions to an endowment created at a Minnesota law school in honor of Representative James L. Oberstar, Democrat of Minnesota, chairman of the House Transportation Committee.

Separately, the company’s lobbyist in Washington has met with Mr. Oberstar’s staff in the last year seeking his support for changes in federal highway legislation that would result in more widespread use of an FMC product, lithium nitrate, in road projects to prevent cracking.

An FMC spokesman said in a statement that the donations are unrelated to the company’s lobbying pitch, and they were not requested by Mr. Oberstar. Still, the lobbyist, Lizanne Davis, said she was pleased with his office’s response.

“They were interested in hearing what we had to say,” she said.

Unlike Mr. Rangel, Mr. Oberstar and most of the lawmakers being honored with university centers avoid requesting donations themselves, instead leaving such pleas up to staff from the universities or charities involved, aides said in interviews this week.

But spokesmen for six of the members — Mr. Oberstar; Mr. Clyburn; Mr. Hastert; Senator Thad Cochran, Republican of Mississippi; former Representative John P. Murtha, Democrat of Pennsylvania; and the former Senate majority leader Trent Lott, Republican of Mississippi — said each of them attended events while in office to announce the creation of the programs or to thank donors.

Some, including Mr. Oberstar and Mr. McConnell, asked Congressional ethics officials for “advice letters” to authorize their participation in the endowment programs, their aides said in interviews.

Ethics experts in Washington argue that if lawmakers play even a modest role in such programs — like authorizing the use of their name and appearing at events celebrating the endowment — it still creates an appearance of a conflict.

“The simple fact is these things should not be named after people when they are in office.” said Norman J. Ornstein, an expert in campaign finance at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, a conservative-leaning research group. “We all know what is going on here: the donors are trying to influence the lawmakers.”

Ron Nixon contributed reporting.

MORE IN POLITICS (4 OF 47 ARTICLES)

White House Memo: Turning a Crisis Into an Opportunity

ClosePayback Time - For Denver Schools, a Financing Deal Takes a Bad Turn

Exotic Deals Put Denver Schools Deeper in Debt

By GRETCHEN MORGENSON

In the spring of 2008, the Denver public school system needed to plug a $400 million hole in its pension fund. Bankers at JPMorgan Chase offered what seemed to be a perfect solution.

The bankers said that the school system could raise $750 million in an exotic transaction that would eliminate the pension gap and save tens of millions of dollars annually in debt costs — money that could be plowed back into Denver’s classrooms, starved in recent years for funds.

To members of the Denver Board of Education, it sounded ideal. It was complex, involving several different financial institutions and transactions. But Michael F. Bennet, now a United States senator from Colorado who was superintendent of the school system at the time, and Thomas Boasberg, then the system’s chief operating officer, persuaded the seven-person board of the deal’s advantages, according to interviews with its members.

Rather than issue a plain-vanilla bond with a fixed interest rate, Denver followed its bankers’ suggestions and issued so-called pension certificates with a derivative attached; the debt carried a lower rate but it could also fluctuate if economic conditions changed.

The Denver schools essentially made the same choice some homeowners make: opting for a variable-rate mortgage that offered lower monthly payments, with the risk that they could rise, instead of a conventional, fixed-rate mortgage that offered larger, but unchanging, monthly payments.

The Denver school board unanimously approved the JPMorgan deal and it closed in April 2008, just weeks after a major investment bank, Bear Stearns, failed. In short order, the transaction went awry because of stress in the credit markets, problems with the bond insurer and plummeting interest rates.

Since it struck the deal, the school system has paid $115 million in interest and other fees, at least $25 million more than it originally anticipated.

To avoid mounting expenses, the Denver schools are looking to renegotiate the deal. But to unwind it all, the schools would have to pay the banks $81 million in termination fees, or about 19 percent of its $420 million payroll.

John MacPherson, a former interim executive director of the Denver Public Schools Retirement System, predicts that the 2008 deal will generate big costs to the school system down the road. “There is no happy ending to this,” Mr. MacPherson said. “Hindsight being 20-20, the pension certificates issuance is something that should never have happened.”

A spokesman at JPMorgan, which led the Denver deal, declined to comment. Royal Bank of Canada, which acted as the school system’s independent adviser even though it participated in the debt transaction, declined to comment. Denver school officials said that they had agreed to sign a conflict waiver with Royal Bank of Canada.

Denver isn’t the only city confronted with budgetary woes aggravated by esoteric financial deals that Wall Street peddled in the years before the credit crisis. Banks have said the deals were appropriate for the issuers and that no one could have predicted the broad financial collapse that put pressure on the transactions.

Still, some municipalities have found such arguments wanting and are pushing back.

Last March, the Los Angeles City Council told its treasurer and city administrative officer to renegotiate interest-rate deals the city had used to try to lower its debt payments with the banks that sold them. “If they are unwilling to renegotiate, then those financial institutions should be excluded from any future business with the City of Los Angeles,” noted a report by the City Council.

In Pennsylvania, some school districts have unwound interest-rate deals, and the state’s auditor general, Jack Wagner, has urged other issuers to follow suit. “For the sake of Pennsylvania taxpayers, I call on the other school districts that have entered into similar swaps contracts to get out of these risky agreements as soon as they possibly can,” he said in a statement in February.

Financial stress from these deals could not come at a worse time for cities, towns and school districts already saddled with high costs and falling revenue. Although it is difficult to tally how many public entities entered into interest-reduction deals, a recent analysis by the Service Employees International Union estimated that over the last two years, state and local governments have paid banks that arranged these transactions $28 billion to get out of the deals, seeking to avoid further crushing payments.

Many transactions remain on public issuers’ books. S.E.I.U. estimates that New Jersey would have to pay $536 million to get out of its derivatives contracts, while California faces $234 million in such payments. Chicago is looking at $442 million in termination fees to unwind its transactions, and Philadelphia would have to pay $332 million.

Both Mr. Bennet, whom the White House has praised for his innovative approach to education, and Mr. Boasberg defend the deal they recommended in Denver back in 2008. They say that it has saved the school district $20 million it would have otherwise had to pay to cover the pension shortfall, and they maintain that no one could have predicted the credit crisis of 2008 that elevated the deal’s costs.

But the savings cited by the two men do not take into account termination fees associated with the complex deal. And had the school district issued fixed-rate debt, Wall Street would not have received the cornucopia of fees embedded in the more complex deal.

While the expenses associated with more complex transactions vary depending on the terms of the deal, Denver offers an example of the additional costs they can impose. So far, Denver has paid about $9.7 million more in fees for its deal than it would have had it chosen a simpler transaction.

Joseph S. Fichera, chief executive of Saber Partners, a financial advisory firm that specializes in structured finance, said that the type of transaction pursued by the Denver schools was a false solution for what the issuers want to achieve — lower long-term costs — because the banks selling the deals rarely quantified all of the potential risks involved.

“The issuer made a simple financing highly complex and took on substantial risk without knowing how large its downside could be,” he said, referring to the Denver deal. “The advisers and bankers may have disclosed that there were risks, but apparently did not help the issuer truly understand them. They typically present economic outcomes to the issuer only on projected savings and assume away any chance of the risks happening.”

THE PROBLEM

$400 Million Gap

In a Pension Fund

The Denver public schools needed to do financial contortions because, like many other public agencies nationwide, its pension plan did not have enough funds to meet the payments due to retirees. And for years, the school system had not met its required annual pension payments to ensure a fully funded plan; by 2007, the school system faced a $400 million gap.

The school system solicited advice from several banks on how to handle this problem and ultimately decided to issue bonds that allowed it to refinance its existing debt of $300 million, which had a fixed interest rate. It also raised an additional $450 million, most of which went into the pension to fill the gap in that plan. Together, $750 million was raised using the riskier pension certificates.

The Denver certificates contained debt issues that had variable rates and were to be resold to investors in weekly auctions; the arrangement carried an annual interest rate of around 5 percent, not counting fees and costs associated with that type of debt. Fixed-rate debt would have cost 7.2 percent.

Denver schools had issued pension certificates before, but this time the banks added a little spice to the recipe: an interest-rate swap that made the variable debt mimic a fixed-rate instrument. If prevailing rates fell, the school system would have to make up the difference to the banks. But if interest rates rose, the swap would protect the school system from having to pay higher debt costs.

It was a heady brew, one that required an unusual amount of financial expertise to assess. In that regard, Denver had an apparent advantage: Mr. Bennet and Mr. Boasberg.

Unlike many school district officials, both men were financially sophisticated and had worked together in the private sector. Mr. Bennet handled investments and structured financial deals for the Anschutz Investment Company, a private concern owned by the billionaire Philip Anschutz that has stakes in telecommunications and oil. Mr. Boasberg, meanwhile, was a deal maker in mergers and acquisitions at Level 3 Communications, a telecommunications concern.

“We looked at what the risks were,” said Mr. Boasberg, who has been superintendent of the Denver public schools system since early 2009.

But according to several members of the board of education, the bankers’ presentations for the 2008 debt deal outlined its risks only in broad terms, discussing, for example, what would happen if interest rates shifted or the economy weakened a bit. The banks provided no full-blown worst-case situations to the board, focusing instead on the transaction’s upside: lower debt costs and a potential saving of $129 million in pension costs over the next 30 years.

School board members also said that bankers had not discussed problems in the variable-rate debt market that arose the previous year — a development that would have alerted them to troubles they might have had securing a manageable rate on the debt that they were refinancing.

Nor, they said, had the bankers discussed the outright collapse of trading in auction-rate securities, a $330 billion market that ran aground in mid-February 2008. Auction-rate securities are very similar to the variable-rate debt the Denver schools were considering at the time; both types of securities involve periodic auctions sponsored by financial institutions to determine what interest rates will be paid by the issuer.

Like the structural weaknesses in the variable-rate market, turmoil in the auction-rate market should have been a warning sign for the Denver school system and its financial stewards. But according to board members, its bankers and advisers never sent up warning flares of this sort.

“I think there was discussion around financial markets as a whole,” said Bruce Hoyt, a board member since 2003 and treasurer at the time the deal was done. “I don’t recall specific discussions about the freezing of auction-rate securities.”

In the end, Denver became ensnared in the financial maelstrom that was stirring even before it restructured its debt and that gathered force as the credit crisis deepened through the summer and fall of 2008. Prevailing interest rates collapsed, and the market for the Denver public school system’s debt shrank markedly.

Denver’s funding costs rose further when Dexia, a Franco-Belgian company that had facilitated the transaction and insured the pension certificates, ran into trouble. Worried about Dexia’s financial position, investors fled any securities the company had insured, including Denver’s debt.

In the end, a deal that JPMorgan said would have an interest rate of around 5 percent spiked to 8.59 percent during its first fiscal year, and has since settled down to an average rate of 7.12 percent today.

THE MISSTEP

Locked In for Years

As a Deal Sours

Financial advisers say that deals like Denver’s might work for some issuers. But they say that their complexity can mask the fact that they often require issuers to give up far more than they get in return.

Like a homeowner, Denver essentially started out with the equivalent of a standard, fixed-rate mortgage that allowed it to refinance if interest rates fell. But the 2008 deal gave that up for the equivalent of a 30-year loan with a lower rate but significant penalties and costs if investor interest in the debt declined, as it did once the credit crisis kicked in.

Moreover, refinancing was extremely costly, given the hefty termination fees.

While such deals have become common in public finance circles, they are rare in the private sector. If corporations issue such debt, they will typically limit their terms to five years, which gives them room to maneuver as economic circumstances evolve.

Agreeing to be locked into a 30-year contract, as public entities have done, is especially costly because getting out of it requires paying penalties to the banks for every remaining year of the transaction.

Andrew Kalotay, founder of Andrew Kalotay Associates, a debt management advisory firm, said a deal like Denver’s would be highly unusual among private sector issuers like corporations because they recognized the pitfalls of locking themselves into an arrangement for 30 years.

“I’m not aware of any corporations trying to get a better fixed rate” by issuing long-term instruments such as those used by Denver. “Why would the school district want to do this transaction with all the attendant risks of mispricing and the possibility of unfavorable unwind costs when they could have done a conventional, taxable fixed-rate deal?” he asked.

Bankers, however, love these deals. In addition to the enormous termination fees they can snare, bankers also get remarketing fees and swap advisory fees.

Termination fees, however, top them all. Like the punishing prepayment penalties some homeowners have to come up with when paying off a mortgage early, termination fees on deals like Denver’s are essentially charges levied to rewrite the terms of a contract.

To some issuers, termination fees feel easier to swallow if they pay for it by issuing yet another round of debt, like a consumer using one credit card to pay the penalty charges on another. But even though no upfront cash is paid out, yet another layer of debt is incurred, adding to the cost of getting out of the deals.

Denver is considering paying its termination fees in this fashion, Mr. Boasberg said. It was unclear what the interest rate would be on the new debt, but he maintained that the school system would unwind the transactions only if it were economical and the interest rate on the debt were low enough to offset the termination fees.

Had Denver issued a standard, fixed-rate bond in 2008, it would not be facing termination fees now. While it is possible that the annual costs of the Denver deal will come down in the future, they are now roughly in line with what the school system would have paid in a fixed-rate transaction.

Jeannie Kaplan, a board of education member for almost five years, supported the 2008 deal but now regrets it because of its costs and complexity. “Bennet and Boasberg had been presented as financial saviors of the Denver school system, and I sat there wanting to believe what they were saying,” she said. “The board probably should have had their own financial consultant.”

Mr. Boasberg said critics of the deal were politically motivated, pointing to the close primary runoff pitting Mr. Bennet, the former superintendent, against Andrew Romanoff, another Democrat, for a place on the ballot for the Senate in the November elections. But Ms. Kaplan said she started questioning the deal before Mr. Bennet was appointed to the Senate in early 2009.

The school system’s 2008 refinancing is one of several issues that have come up in the runoff, including campaign financing, general integrity issues and Washington effectiveness.

Mr. Bennet became superintendent of the Denver schools in 2005 after he left the Anschutz organization to work for the mayor of Denver, John Hickenlooper.

From the campaign trail in mid-July, Mr. Bennet reiterated his support of the deal, saying that it had achieved the school system’s goal of improving its cash flow and merging with Colorado’s Public Employees’ Retirement Association, which meant the schools no longer had to pay 8.5 percent interest on its annual pension shortfall.

“Despite going through the worst recession since the Great Depression, we did that,” he said in a statement.

THE RESULTS

Another Shortfall,

And Cloudy Future

As Denver weighs its refinancing problems, it faces another conundrum: the money the city raised to shore up its pension fund has turned out to be inadequate because of the stock market’s plunge.

The fund turned in a dismal performance in the credit crisis — as was the case with most such funds — losing almost twice the $400 million borrowed by the school district to plug the pension gap. As a result, the school system’s pension shortfall recently stood at around $386 million, only slightly lower than it was two years ago, and even though $400 million had been funneled into it in 2008.

While the pension’s merger with the state system allows Denver’s school system to avoid paying interest on shortfalls, that benefit is temporary. If a shortfall still exists in 2015, the merger requires that it be closed.

Mr. Boasberg maintains that the deal has allowed Denver to hire teachers while other school districts are cutting back. But Henry Roman, president of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, said that fewer teachers had been hired this year than in previous years.

Some board of education members fear that the human costs of Denver’s exotic refinancing deal are yet to be fully realized — and when they are, it will be in classrooms.

Ms. Kaplan says she is particularly concerned about the impact of having to fund the Denver school’s pension plan fully in 2015 if investment losses have not been recouped by then.

“How is that going to affect kids and teachers and classrooms?” she asked. “It makes it difficult for board members to do a budget now.”